Sub-Saharan African migration into Morocco, Modern Ghana.

By Max Berengaut

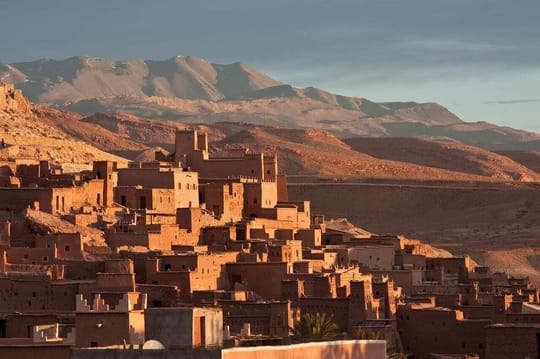

Entering Morocco, Sub-Saharan African migrants find themselves at a crossroads. There is the promise of an economic future waiting for them in Europe, but the path to it is perilous. They require either an assurance of asylum status or some familial relationship with a European in order to enter into Europe without any problems. Unfortunately, many will have neither, forcing them into dangerous and irregular means of entry into Europe, or at times leading them to stay in Morocco. While Morocco has for most of its history been an emigration country, its geographic usefulness puts it at the forefront of migration in the Mediterranean, between one of the most populous emigration centers in the world, Sub-Saharan Africa, and one of the most popular immigration destinations in the world, Western Europe.

A hold on this northern flow of migration from Sub-Saharan Africa is unlikely, as the immigration routes have been long established, and population growth in Sub-Saharan Africa continues to rise steadily. In countries with established pathways of migration, like Ghana and Nigeria, it was found that nearly one third of all respondents indicated that they were going to leave their home country for Europe or the United States sometime in the next five years (Connor). Further research from Syed Ali in a chapter from his book entitled ‘Maligned Migrants’, explains that “while Western European countries put great restrictions on further labor migration, the [migrant] population kept growing through family reunification, and in the 1990s, through the admission of refugees.” The first initial waves of migration create a difficult to control stream of further migration, and with governmental programs like family reunification simplifying the legal complications that tend to decentivize migration, over a million Sub-Saharan Africans have moved to Europe since 2010, mostly seeking asylum or irregularly migrating (Connor). In 2018, there were more Mediterranean migrants entering Spain than any other European country, naturally signifying that Morocco was seen as the leading transit country for African migrants attempting to enter into Western Europe.

Refugees and asylum-seekers are people who leave their homes because they are fleeing from war or persecution. However, to be granted either refugee or asylum status at their destination country, they need to prove legally that they had a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or social group affiliation. While hundreds of thousands of Sub-Saharan African undocumented migrants have been classified as refugees in the United States by the UNHCR, there are many more in Europe who have struggled to receive the same classification. Furthermore, most western countries use refugee quotas, allowing the reception or resettlement of a sometimes contentious number of refugees every year. This phenomenon can exclude asylum-seekers who find themselves outside the quite narrow legal definition of refugee. For poor migrants desperate for any source of income, the legal complexities of their situation can often be difficult to fully understand, especially in countries where their legal status can be easily manipulated by those who exploit their relative lack of knowledge.

While their situation is contextually quite different, Sub-Saharan African migrants who stay in Morocco struggle with many of the same issues as their counterparts in Western Europe. While there are many Sub-Saharan African migrants who immigrate specifically to Morocco, there is also a large number of them who find themselves with no other choice but to remain in Morocco as their window of opportunity to enter Western Europe subsides. In a feature article for the Migration Policy Institute, Driss El Ghazouanoi says that ‘stuck’ Sub-Saharan African migrants have become a familiar sight to many Moroccans, most of them living without proper documents. As of now, there are roughly 700,000 Sub-Saharan migrants living in Morocco, making up about 2% of the mostly homogenous population (MPI). The Moroccan government has committed to helping these migrants, writing and passing laws that provide pathways to full citizenship, but there will be a long process to fully acclimate them into Moroccan society. There have been some reports of social discontent towards migrants (Alami), and while the Moroccan government will need to keep an eye on the rise of hate that is often associated with immigration growth, their larger issue is likely the struggle for proper documentation.

The Legal Aid Clinic (CFJD), housed at the Faculty of Social, Legal, and Economic Sciences at University Sidi Mohamed Ben Adbellah in Fes, is one of the few opportunities for migrants currently living in Morocco to be provided the proper legal assistance that would allow them to have a source of income while living in Morocco. With funding from the National Endowment for Democracy and the Middle East Partnership Initiative, the CJFD trains law students to provide pro bono legal aid to those who are in need of it most. While there are country-wide economic issues in Morocco, such as unemployment and hard-to-access social services, there are still opportunities for migrants to carve out a life for themselves in the country, such as in the Fes-Meknes region, whose decreasing urban population growth could potentially be mitigated by a rise in the migrant population (Oxford Business Group).

For many Sub-Saharan African migrants, their future legal and economic situations are frustratingly insecure. There is a dearth of resources available to them, not only in Morocco but in all of Western Europe. The CJFD in Fes is, therefore, a helpful option for migrants who need guidance and support as they transit, integrate into Moroccan society, or prepare to repatriate back to their home countries.

Max Berengaut is a student at the University of Virginia and an Intern at the High Atlas Foundation.