An Interview with Si Mbark, the Caretaker of the Former Talmud Torah School in Essaouira

World Interfaith Harmony Week

An Interview with Si Mbark, the Caretaker of the Former Talmud Torah School in Essaouira

Essaouira, Morocco

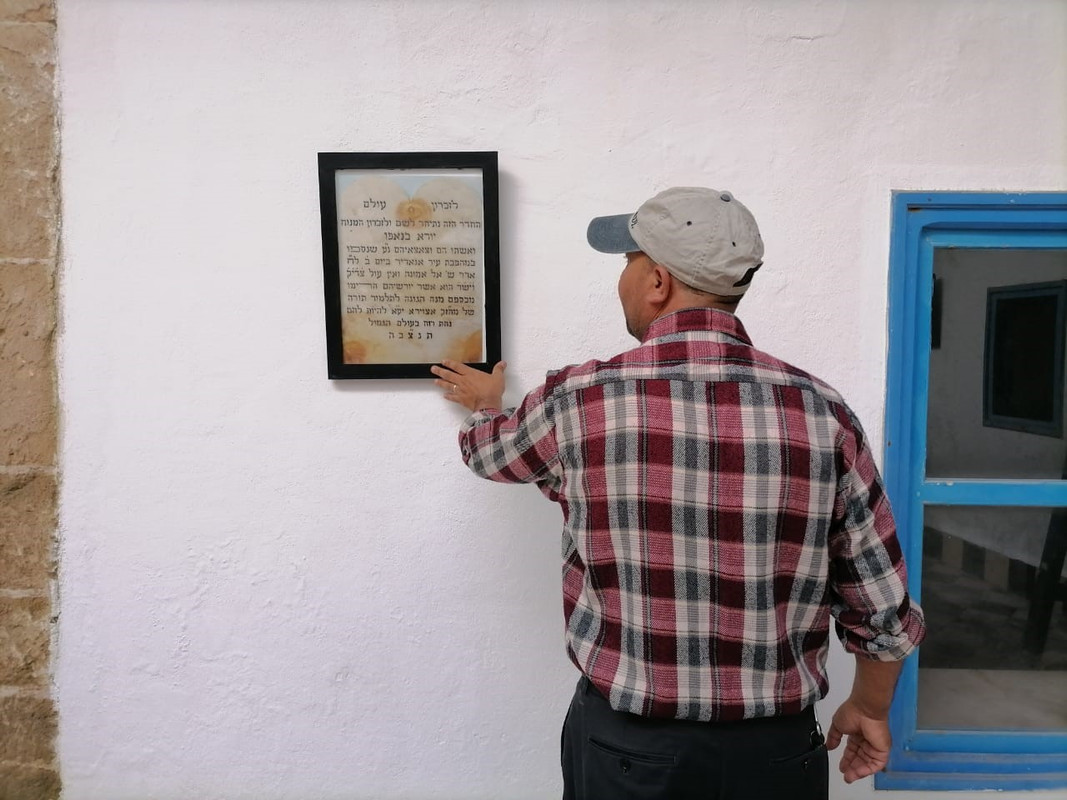

Si Mbarek at the former Talmud Torah School. Photo: Amal Mansouri/ HAF

About the Talmud Torah of Essaouira

Compared to other Jewish heritage sites, the Talmud Torah school in Essaouira is not very frequently visited. “I could say that one out of three tourist groups that pass by the Mellah (Jewish quarter) come and visit it. Now that its name has changed, visitors find it hard to locate.” Si Mbark’s statement didn’t surprise me, as I, myself, had haphazardly stumbled upon this place during a conversation with an Essaouira local.

Si Mbark is the caretaker of the former Talmud Torah School in Essaouira, which was founded in 1888. When the school was in operation, the ground floor housed the kindergarten, and the canteen and classrooms were the next floor up. The school closed in the 1960s after the Jew residents there left Morocco en masse, and the space was transformed into a shelter for the last few Jewish families who stayed in the city. Si Mbark has guarded the space for almost 14 years–since it became Dar Al Hay (“Neighborhood House” in English), as it is currently known. Dar Al Hay serves as a headquarters and meeting space for a number of local civil society organizations working with children, women, and youth, in the education, health, culinary arts, and other social sectors. As part of the rehabilitation project in the old medina of Essaouira, the building is currently under restoration, but the ground floor remains open for visitors.

Si Mbark and Sacred Responsibility

Si Mbark originally hails from the Ait Lahcen tribe from the south of Morocco. His father and grandfather were nomads. As part of their journey, they one day decided to spend time near Essaouira. When his grandfather passed away and they lost their cattle due to drought, Mbark’s father decided to give up his nomadic lifestyle and explore job opportunities in Essaouira. He tried different jobs, working as a carrier and then with a Jewish man named Lyahoo, who taught him how to sew mattresses. The Jewish man trusted Mbark’s father from the get-go, letting him manage his rental properties and recommending his services to other Jewish families in Essaouira.

Mbark’s father’s dedication and loyalty earned him further the trust of the Jewish community, and as a part of his job, he began to assist Jewish families with looking after their properties, including the Talmud Torah school. Following the departure of the Jewish community and the school’s closure, Mbark’s father was offered the option to move into the school to settle there for free and ensure the maintenance of the place. At that time, in addition to Mbark’s family, three Jewish families lived in the building. They stayed in Essaouira until they passed away and were buried in the nearby Jewish cemetery, as Si Mbark recalls. After working for almost 50 years with the Jewish community, Mbark’s father also passed away, and he inherited the job as the caretaker of the former Talmud Torah. Si Mbark, who is not married, is the only member of his family who still resides in the building and guards it today. His siblings chose to move out a long time ago.

|

|

|

From left to right: Si Mbark’s father in the former Talmud Torah of Essaouira; Si Mbarek stands in the same spot years later as its current guardian, Essaouira, Morocco. Photo courtesy of Si Mbark

Home: A Place of Memory

“I’ve lived here my entire life. All my childhood memories are in this place, so I couldn’t leave,” Si Mbark said, smiling when he was asked about the reason he decided to stay and look after the building. “It’s where I feel most at peace and comfortable. This is my home. It’s where it all started. I don’t want to live anywhere else. Also, the fact that I inherited this job from my father makes me more responsible for it, and I want to show my gratitude to the Jewish community, friends and neighbors, who were of great help to us.”

Touring the first floor and conversing with Si Mbark about his memories with his Jewish neighbors with whom he once shared this space provoked in him a strong sense of nostalgia. “I remember that the last Jewish person who lived in the school passed away in 1999. Our Jewish neighbors and friends were kind and generous. Having different faiths and cultures didn’t divide us. Regardless of our differences, we were simply friends who had mutual respect for each other. I remember that they would not eat in public during Ramadan out of respect for the Muslim people, and the same went for us on Shabbat. We would try to help them and provide them with what they needed on that day. We celebrated our holidays together, invited each other to take part, and exchanged food made on special occasions. Moreover, in the canteen of the former Jewish school, they reserved a day just for the Muslim people.”

Si Mbark has had the chance to meet many visitors who have come searching specifically for the school because they used to study there. In such cases, they have often become very emotional while sharing their memories with him. While talking with him, he described how it is now difficult for visitors to find their way to the school. “The place lacks signage that refers to it as the old Talmud Torah. Now that the name has changed, people don’t pay attention to it, or they think that it was demolished during the renovation project in the Mellah. It would be nice if the sign is written in Hebrew, Arabic, and French.”

The need to celebrate the history of such places stems from the role they play as repositories of memories, which reflect the historical plurality of communities whose diverse inhabitants lived side by side for generations. In the case of the former Talmud Torah school, Si Mbark’s suggestion is to curate an exhibition of the old Torahs, books, and archives from the library that were used during the school’s operation.

—

This article is part of a series of interviews that celebrates Interfaith Harmony Week (February 1-7, 2023) and have been facilitated by the USAID Dakira program, which is implemented by the High Atlas Foundation and its partners and aims to strengthen inter-religious and inter-ethnic solidarity through community efforts that preserve cultural heritage in Morocco.

The article was completed with the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the High Atlas Foundation is solely responsible for its content, which does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the Government of the United States.